The ln command is one of those Linux tools you don’t fully appreciate until you need it. And when you do, it’s usually at the worst possible moment — trying to manage multiple config file versions or untangling a web of file references across your system.

I remember my first time wrestling with broken symlinks on a production server. It wasn’t pretty. But that experience taught me how powerful links can be when you understand them properly.

This guide will show you exactly how to use the ln command in Linux to create both symbolic and hard links. You’ll learn the key differences, see practical examples, and avoid the common mistakes that trip up even experienced admins.

What is the ln Command in Linux?

The ln command creates links to files and directories. Think of it as creating multiple access points to the same data without duplicating it.

Instead of making copies that eat up disk space, you’re essentially creating pointers. The data lives in one place. The links just tell the system where to find it.

Understanding Links vs Copies

When you copy a file with cp, you create a completely separate file. Changes to one don’t affect the other. Both files use disk space.

Links work differently. They reference the same underlying data. Edit through any link, and you’re editing the original. This approach saves space and keeps everything synchronized.

If you’re managing disk space carefully (check our guide on checking disk usage), links become your best friend.

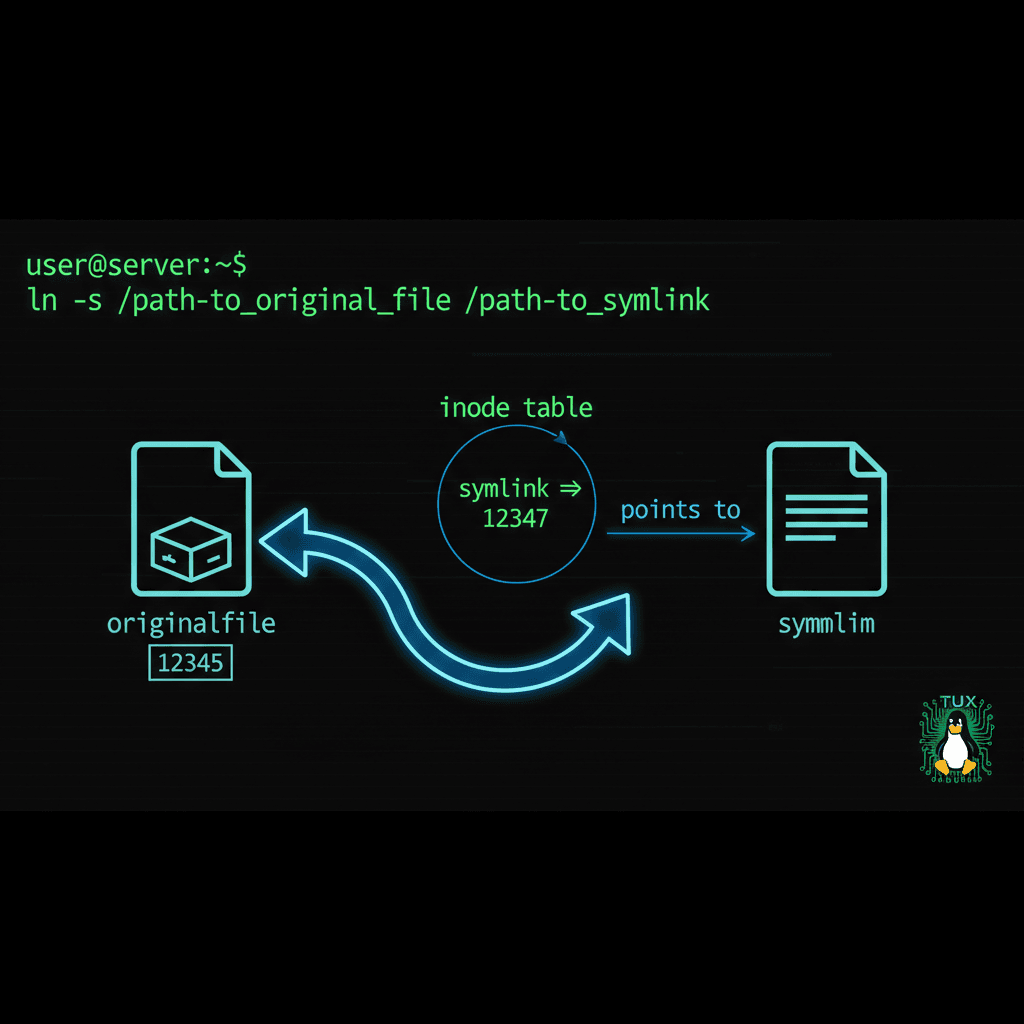

How ln Interacts with Inodes

Here’s where it gets interesting. Every file on a Linux filesystem has an inode — a unique data structure that stores file metadata and points to the actual data blocks.

When you create a link, you’re either pointing directly to that inode (hard link) or creating a special file that points to the original path (symbolic link). The distinction matters more than you might think.

When You Need ln Instead of cp

Use ln when you need:

- Multiple access points: Same file accessible from different directories

- Space efficiency: Reference data without duplicating it

- Synchronized changes: Edit once, reflect everywhere

- Version management: Quickly swap between software versions

Symbolic Links vs Hard Links: Key Differences

This is where most people get confused. Both create links. But they work in fundamentally different ways.

Understanding this difference will save you from debugging headaches later. Trust me on this one.

What Are Hard Links?

A hard link is another name for the same file. Literally. It points directly to the same inode structure in ext4 (or whatever filesystem you’re using).

Key characteristics of hard links:

- Same inode number as the original

- Must exist on the same filesystem or partition

- Cannot link to directories

- Data persists until ALL links are deleted

- No distinction between “original” and “link” — they’re equal

That last point is powerful. Delete the “original” file? Doesn’t matter. The data survives through any remaining hard link.

What Are Symbolic Links (Symlinks)?

Symbolic links work like shortcuts. They’re separate files that contain a path to the target.

According to the POSIX symlink specification, the target doesn’t even need to exist when you create the link.

Symlink characteristics:

- Own inode number (different from target)

- Can cross filesystem boundaries

- Can link to directories

- Becomes broken if target is deleted or moved

- Shows clearly as a link in

ls -loutput

When to Use Each Type

Use Hard Links When:

- Files are on the same filesystem

- You want data to persist even if “original” is deleted

- You need maximum performance (one less level of indirection)

- You’re creating backup references to important files

Use Symbolic Links When:

- Linking across different filesystems or partitions

- Linking to directories

- You need to see the link relationship clearly

- Managing software version switches

Basic ln Command Syntax and Options

Let’s get into the actual commands. The ln command man page covers every option, but here’s what you’ll use 95% of the time.

Creating Hard Links (Default Behavior)

The basic syntax creates a hard link:

ln TARGET LINK_NAMEExample — create a hard link called backup_config pointing to app.conf:

ln /etc/myapp/app.conf /etc/myapp/backup_configBoth files now point to the same inode. Same data, two names.

Creating Symbolic Links with -s Flag

Add the -s flag for symbolic links:

ln -s TARGET LINK_NAMEExample — create a symlink in your home directory pointing to a log file:

ln -s /var/log/myapp/current.log ~/app_logEssential Command Options

Here are the options you’ll actually use:

- -s: Create symbolic (soft) link instead of hard link

- -f: Force — remove existing destination files

- -n: Treat symlink to directory as normal file (don’t follow)

- -v: Verbose — show what’s being created

- -r: Create relative symbolic links

- -i: Interactive — prompt before removing existing files

How to Create Symbolic Links (Soft Links)

Symlinks are what you’ll use most often. They’re flexible, visible, and work across filesystem boundaries.

Basic Symlink Creation

The pattern is simple: target first, then link name.

ln -s /path/to/original /path/to/linkReal example — make Python 3.11 accessible as just “python”:

ln -s /usr/bin/python3.11 /usr/local/bin/pythonNow typing python runs Python 3.11.

Linking to Directories

Symlinks can point to directories. This is incredibly useful for organizing files without moving them.

ln -s /var/www/projects/client_alpha ~/current_projectNow cd ~/current_project takes you straight to that client’s directory. When you switch clients, just update the symlink.

Using Absolute vs Relative Paths

This is critical. Get it wrong and your links break mysteriously.

Warning: Relative paths are relative to the LINK location, not your current directory. This trips up everyone.

Absolute paths (recommended) always work:

ln -s /home/user/projects/app/config.yaml /etc/app/config.yamlRelative paths can break if files move:

ln -s ../projects/app/config.yaml /etc/app/config.yamlUse absolute paths unless you have a specific reason not to. Your future self will thank you.

How to Create Hard Links

Hard links have restrictions, but they’re powerful when used correctly.

Basic Hard Link Creation

Drop the -s flag:

ln /path/to/original /path/to/hardlinkExample — create a hard link for a critical config file:

ln /etc/nginx/nginx.conf /etc/nginx/nginx.conf.backupNow even if someone deletes nginx.conf, the data survives in the backup link.

Verifying Hard Links with ls -i

How do you confirm two files are hard-linked? Check their inode numbers:

ls -li /etc/nginx/nginx.conf /etc/nginx/nginx.conf.backupIf the first number (inode) matches, they’re hard links to the same data.

You can use the find command to locate all hard links to a specific inode:

find /etc -inum 12345678Hard Link Limitations to Know

Before creating hard links, remember these constraints:

- Same filesystem only: Both files must be on the same mounted filesystem

- No directories: Only regular files can be hard-linked

- No cross-partition: Won’t work across different partitions

- Permissions: All links share permissions (see file permissions with chmod)

Common ln Command Use Cases

Theory is fine, but let’s see how the ln command solves real problems.

Creating Shortcuts to Frequently Used Files

Put commonly used scripts in your PATH without moving them:

ln -s /home/user/scripts/deploy.sh /usr/local/bin/deployNow deploy works from anywhere. The actual script stays in your organized project folder.

Managing Multiple Software Versions

This is a classic sysadmin technique. Install multiple versions, symlink to the active one:

# Install multiple Node.js versions

/opt/node-18.0.0/

/opt/node-20.0.0/

/opt/node-22.0.0/

# Symlink active version

ln -sf /opt/node-20.0.0 /opt/node

# Add to PATH

export PATH="/opt/node/bin:$PATH"Switching versions? Just update the symlink. You can even automate with cron for scheduled version switches.

Organizing Log Files Without Duplication

Centralize logs from multiple locations:

mkdir -p /home/admin/all_logs

ln -s /var/log/nginx/access.log /home/admin/all_logs/nginx_access

ln -s /var/log/app/production.log /home/admin/all_logs/app_prod

ln -s /var/log/mysql/error.log /home/admin/all_logs/mysql_errorOne directory to check. No duplication. Changes reflect instantly.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

I’ve made all of these. Learn from my pain.

The Relative Path Trap

This is mistake number one. You’re in /home/user and run:

ln -s data/config.yaml /etc/app/configLooks fine. Works initially. Then you move /home/user/data and everything breaks.

The fix? Always use absolute paths:

ln -s /home/user/data/config.yaml /etc/app/configBroken Links (Dangling Symlinks)

Symlinks can point to files that don’t exist. This creates “dangling” or broken links.

Find all broken symlinks in a directory:

find /path/to/search -xtype lThe -xtype l option specifically finds broken symbolic links. Clean these up periodically to avoid confusion.

Accidentally Creating Links in Wrong Locations

Before creating any link, always verify your location:

pwd

ls -laMake sure you’re where you think you are. I’ve created links in the wrong directory more times than I’d like to admit.

Use the -v flag to see exactly what ln is doing:

ln -sv /source/file /destination/linkTroubleshooting and Managing Links

Links are created. Now how do you manage them?

Finding All Links to a File

For symlinks, search by name or use readlink:

# See where a symlink points

readlink /path/to/symlink

# Follow the complete chain

readlink -f /path/to/symlinkFor hard links, you need the inode number:

# Get inode number

ls -i /path/to/file

# Find all files with that inode

find /search/path -inum 12345678Removing Links Without Deleting Target Files

Use rm or unlink to remove links:

rm /path/to/link

# or

unlink /path/to/linkFor symlinks, this removes the link only. The target stays untouched.

For hard links, the data survives until the LAST link is removed. That’s the beauty of hard links — built-in redundancy.

If you’re changing file ownership, note that symlinks can have different ownership than their targets. Use chown -h to change the symlink’s owner specifically.

Checking if a File is a Link

Multiple ways to check:

# Visual inspection (symlinks show ->)

ls -l /path/to/file

# Test in scripts

if [ -L /path/to/file ]; then

echo "It's a symlink"

fi

# Check link count for hard links

ls -l /path/to/file # Second column shows link countThe symlink system documentation explains how various system calls interact with links if you need deeper detail.

Quick Reference:

ln target link— Create hard linkln -s target link— Create symbolic linkls -li file— Show inode numberreadlink link— Show symlink targetfind -xtype l— Find broken symlinksrm link— Remove link (not target)

Mastering the ln command opens up powerful file organization strategies. Start with symbolic links for flexibility. Graduate to hard links when you need that bulletproof data persistence.

If you’re transferring files between systems and need to preserve your link structure, check our guide on rsync for file transfers — it handles links gracefully with the right flags.

The key is understanding when each link type serves you best. Now go create some links. Just remember to use absolute paths.