The first time I saw xargs in a production script, I thought “why not just use a loop?” Then I watched it process 50,000 log files in minutes while my loop-based approach would’ve taken hours. That’s when I understood: xargs isn’t just another command – it’s the bridge between commands that output data and commands that need arguments.

If you’ve ever tried piping find results to rm and wondered why it didn’t work, xargs is your answer. Let’s dig into how this deceptively simple tool can transform your command-line workflow.

What is xargs and Why You Actually Need It

Here’s the thing most Linux tutorials gloss over: not all commands read from standard input. When you pipe data with |, you’re sending it to stdin. But commands like rm, cp, echo, and mkdir expect arguments on the command line, not piped input.

The xargs command converts stdin into command-line arguments. It reads items from standard input and executes a specified command with those items as arguments.

The Problem xargs Solves

Let’s say you want to delete all .tmp files found by find command. Your first instinct might be:

find . -name "*.tmp" | rmThis fails. The rm command sits there waiting for arguments that never come, because it doesn’t read from stdin. This is where xargs steps in:

find . -name "*.tmp" | xargs rmNow xargs takes the output from find and passes it as arguments to rm. Problem solved.

How xargs Differs from Piping

Regular piping sends data to a command’s stdin. The receiving command must be designed to read from stdin (like grep command, sed for text processing, or awk).

The xargs command builds argument lists from stdin and passes them to commands that expect arguments. It also handles batching automatically – if you have 10,000 files, xargs splits them into manageable chunks that don’t exceed system argument limits.

Basic xargs Syntax You Need to Know

The basic pattern is straightforward:

command1 | xargs [options] [command2]If you don’t specify a command, xargs uses echo by default. This is actually useful for debugging:

find . -name "*.log" | xargsThis shows you exactly what arguments xargs would pass to a command, without actually executing anything destructive. I use this pattern constantly before running batch operations.

A simple example to see it in action:

echo "file1.txt file2.txt file3.txt" | xargs touchThis creates three empty files. The xargs command took the space-separated list from stdin and passed each filename as an argument to touch.

Essential xargs Options for Daily Use

After a decade of system administration, these are the xargs options I reach for most often. Master these and you’ll handle 90% of batch processing tasks.

Controlling Arguments per Command (-n)

The -n option limits how many arguments get passed to each command execution. This is crucial when you need one-at-a-time processing:

echo "user1 user2 user3" | xargs -n 1 idThis runs id user1, then id user2, then id user3 as separate commands. Without -n 1, it would run id user1 user2 user3 once, which would fail.

I use this when creating multiple directories with specific permissions:

cat project_dirs.txt | xargs -n 1 mkdir -pReplacing Strings with -I (The Placeholder Method)

The -I option is my favorite xargs feature. It lets you place arguments exactly where you need them using a placeholder (commonly {}):

find . -name "*.conf" | xargs -I {} cp {} {}.backupThis backs up each config file with a .backup extension. The {} placeholder gets replaced with each input item. You can use the placeholder multiple times, which is powerful for complex operations.

Another pattern I use constantly:

cat servers.txt | xargs -I {} ssh {} 'uptime'This checks uptime on multiple servers in one command.

Interactive Confirmation with -p

When you’re about to run something potentially destructive, -p prompts you before each execution:

find . -name "*.tmp" | xargs -p rmThis asks rm ./temp1.tmp?... for each file. It’s saved me from accidental deletions more times than I can count. Use this liberally until you’re absolutely confident in your command.

Handling Files with Spaces (-0)

Here’s where many scripts break: filenames with spaces or special characters. By default, xargs splits on whitespace. Combine find -print0 with xargs -0 to use null characters as delimiters instead:

find . -name "*.mp3" -print0 | xargs -0 -I {} mv {} /music/This handles files like My Favorite Song.mp3 correctly. Always use -print0 and -0 together for file operations. It’s the difference between a script that works on test data and one that works in production.

Real-World xargs Examples That Save Time

Theory is fine, but let me show you the xargs examples I actually use in daily system administration work.

Finding and Processing Files with xargs

Search for a string across all log files modified in the last day:

find /var/log -name "*.log" -mtime -1 -print0 | xargs -0 grep "ERROR"Find large files and get detailed info on each:

find /home -size +100M -print0 | xargs -0 ls -lhThe xargs find combination is fundamental to file operations. They complement each other perfectly – find locates files based on criteria, xargs processes them efficiently.

Batch File Operations

Change file permissions for all shell scripts in a project:

find . -name "*.sh" -print0 | xargs -0 chmod +xCreate multiple project directories from a list:

cat projects.txt | xargs mkdir -pCopy a config file to multiple locations:

echo "server1 server2 server3" | xargs -I {} scp config.yaml {}:/etc/app/These patterns save enormous amounts of time compared to manual operations or writing custom scripts.

Processing Log Files

Compress all logs older than 30 days:

find /var/log -name "*.log" -mtime +30 -print0 | xargs -0 gzipCount total lines across multiple log files:

find . -name "access.log*" -print0 | xargs -0 wc -lExtract specific columns from multiple CSV files:

find /data -name "*.csv" -print0 | xargs -0 -I {} awk -F',' '{print $3}' {}Bulk Renaming and Moving Files

Convert all JPEG files to lowercase extensions:

find . -name "*.JPEG" | xargs -I {} mv {} {}.tmp

find . -name "*.JPEG.tmp" | sed 's/\.JPEG\.tmp$/.jpeg/' | xargs -I {} sh -c 'mv "${1}.tmp" "$1"' _ {}Okay, that’s getting complex. For bulk renaming, I typically use rename or write a small script. But xargs can handle simple cases:

ls *.txt | xargs -I {} mv {} {}.backupParallel Processing with xargs: Speed Up Your Tasks

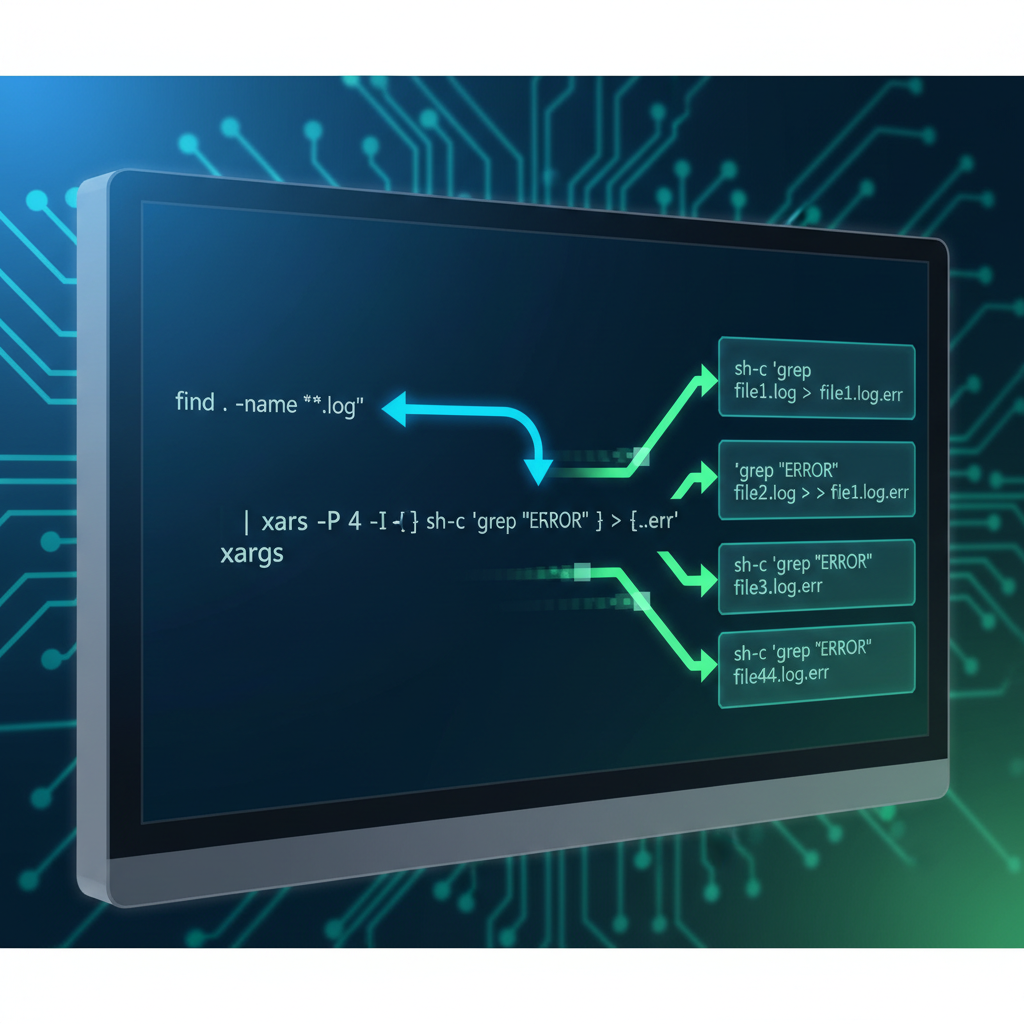

This is where xargs becomes genuinely powerful. The -P option runs multiple commands simultaneously.

The -P Option Explained

By default, xargs runs commands sequentially. With -P N, it runs up to N commands in parallel:

find /var/log -name "*.log" -print0 | xargs -0 -P 4 -I {} gzip {}This compresses four log files at once instead of one at a time. On a multi-core system, this can be dramatically faster.

Use $(nproc) to match your CPU core count:

find . -name "*.jpg" -print0 | xargs -0 -P $(nproc) -I {} convert {} {}.optimized.jpgI’ve seen this approach cut image processing time from 45 minutes to under 10 minutes on an 8-core server.

When Parallel Processing Helps Most

CPU-intensive tasks benefit most from xargs parallel processing when the number of parallel jobs matches CPU cores:

- Image/video conversion

- Compression operations

- Encryption/hashing

- Data parsing and transformation

IO-bound tasks can actually benefit from more parallel jobs than you have cores, because each job spends time waiting on disk or network:

cat urls.txt | xargs -P 20 -I {} curl -O {}This downloads 20 files simultaneously. Most of the time is spent waiting for network responses, not using CPU.

Real performance example from production: Searching 500 log files for error patterns:

# Sequential (baseline): ~120 seconds

find /var/log/app -name "*.log" -print0 | xargs -0 grep "FATAL"

# Parallel with 4 processes: ~35 seconds

find /var/log/app -name "*.log" -print0 | xargs -0 -P 4 grep "FATAL"That’s a 3.4x speedup just by adding -P 4. On systems with more cores, the improvement is even more dramatic.

xargs vs find -exec: Which Should You Use?

This is one of the most common questions I get. Both approaches work, but they have different strengths.

Performance Comparison

The find command has two -exec variants:

find -exec command {} \; runs the command once per file. This is slow because it spawns a new process for every single file:

# Spawns 'rm' 1000 times for 1000 files

find . -name "*.tmp" -exec rm {} \;find -exec command {} + batches files like xargs does. This is much faster:

# Spawns 'rm' once with all files as arguments

find . -name "*.tmp" -exec rm {} +Performance-wise, find -exec {} + and find | xargs are similar. The real advantage of xargs is the -P option for parallel processing, which find -exec doesn’t offer.

When to Use Each One

Use find -exec {} + when:

- You want a self-contained command

- You need the operation to continue even if some files fail

- You don’t need parallel processing

Use find | xargs when:

- You need parallel processing with

-P - You want to stop on first error

- You’re building complex pipelines with multiple processing stages

- You need precise control over argument positioning with

-I

My 2025 workflow: I use find -exec {} + for simple operations and find -print0 | xargs -0 -P for anything that needs speed. For more details on the differences, check out this community discussion on Stack Exchange.

Common xargs Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Let me save you from the mistakes I made learning this command.

Handling Filenames with Spaces

This is the #1 source of broken scripts. Someone creates a file named My Document.txt and your script treats it as two separate files: My and Document.txt.

Always use this pattern for file operations:

find . -name "*.pdf" -print0 | xargs -0 -I {} echo "Processing: {}"The -print0 and -0 combination uses null characters as delimiters. Null characters can’t appear in filenames, so this is bulletproof.

Dealing with Special Characters

Filenames can contain quotes, apostrophes, newlines, and other special characters. The null-delimiter approach handles all of them:

find . -type f -print0 | xargs -0 grep "search term"If you’re not using find, you can generate null-delimited output with other tools using -z or similar options.

Understanding Argument Limits

Every system has a maximum argument length (ARG_MAX). If you try to pass 100,000 filenames to a command, you’ll hit this limit.

The beauty of xargs is that it handles this automatically. It splits input into chunks that fit within system limits. You can check your system’s limit:

getconf ARG_MAXOn modern Linux systems this is usually around 2MB, which is plenty for most operations. If you need explicit control, use -n to set maximum arguments per command:

cat huge_list.txt | xargs -n 100 process_batchAdvanced xargs Techniques for Power Users

Once you’re comfortable with the basics, these advanced patterns open up new possibilities.

Combining xargs with Multiple Commands

Use sh -c to run multiple commands on each item:

find . -name "*.log" -print0 | xargs -0 -I {} sh -c 'echo "Processing {}"; gzip {}; echo "Compressed {}"'This pattern lets you build complex processing pipelines. I use it for automating with cron jobs that need to process files, log results, and send notifications.

A real example from a backup script:

find /data -name "*.db" -mtime -1 -print0 | xargs -0 -I {} sh -c 'mysqldump {} > /backup/{}.sql && gzip /backup/{}.sql'Using xargs in Shell Scripts

In automation scripts, combine xargs with functions for cleaner code:

#!/bin/bash

process_file() {

local file="$1"

echo "Processing: $file"

# Your processing logic here

if some_command "$file"; then

echo "Success: $file"

else

echo "Failed: $file" >&2

return 1

fi

}

export -f process_file

find /data -type f -print0 | xargs -0 -I {} -P 4 bash -c 'process_file "$@"' _ {}

This pattern gives you structured error handling, logging, and parallel execution. Much cleaner than inline command chains.

Dynamic Process Control

For long-running parallel jobs, you can control them with signals. Start a parallel operation in the background:

find /data -name "*.raw" -print0 | xargs -0 -P 8 -I {} convert {} {}.jpg &

XARGS_PID=$!Now you can monitor or control it:

# Check if still running

kill -0 $XARGS_PID 2>/dev/null && echo "Still processing"

# Pause parallel jobs (sends SIGSTOP to child processes)

kill -STOP $XARGS_PID

# Resume

kill -CONT $XARGS_PID

For more complex process management, see our guide on killing processes.

When you need to move the results of batch operations around, tools like rsync integrate well with xargs for efficient file synchronization.

Wrapping Up: xargs as a Force Multiplier

The xargs command is one of those tools that doesn’t look impressive until you understand what it enables. It’s the glue that connects command outputs to command inputs, turning simple operations into powerful batch processing workflows.

The key patterns I use daily:

- Always pair

-print0with-0for file operations - Use

-I {}when you need precise argument placement - Add

-P $(nproc)for CPU-intensive tasks to maximize performance - Start with

-pfor interactive confirmation until you’re confident - Test with

echo(the default command) before running destructive operations

Master these patterns and you’ll handle batch processing tasks that would take hours of manual work or complex scripts. For complete technical details, reference the official xargs man page and GNU Findutils xargs documentation.

The xargs command is part of the GNU Findutils project, maintained alongside find and other essential command-line tools. Together, they form the foundation of Unix pipeline processing that’s been powering automation for decades.

Now go build something efficient. Your future self – the one who doesn’t have to manually process 10,000 files – will thank you.