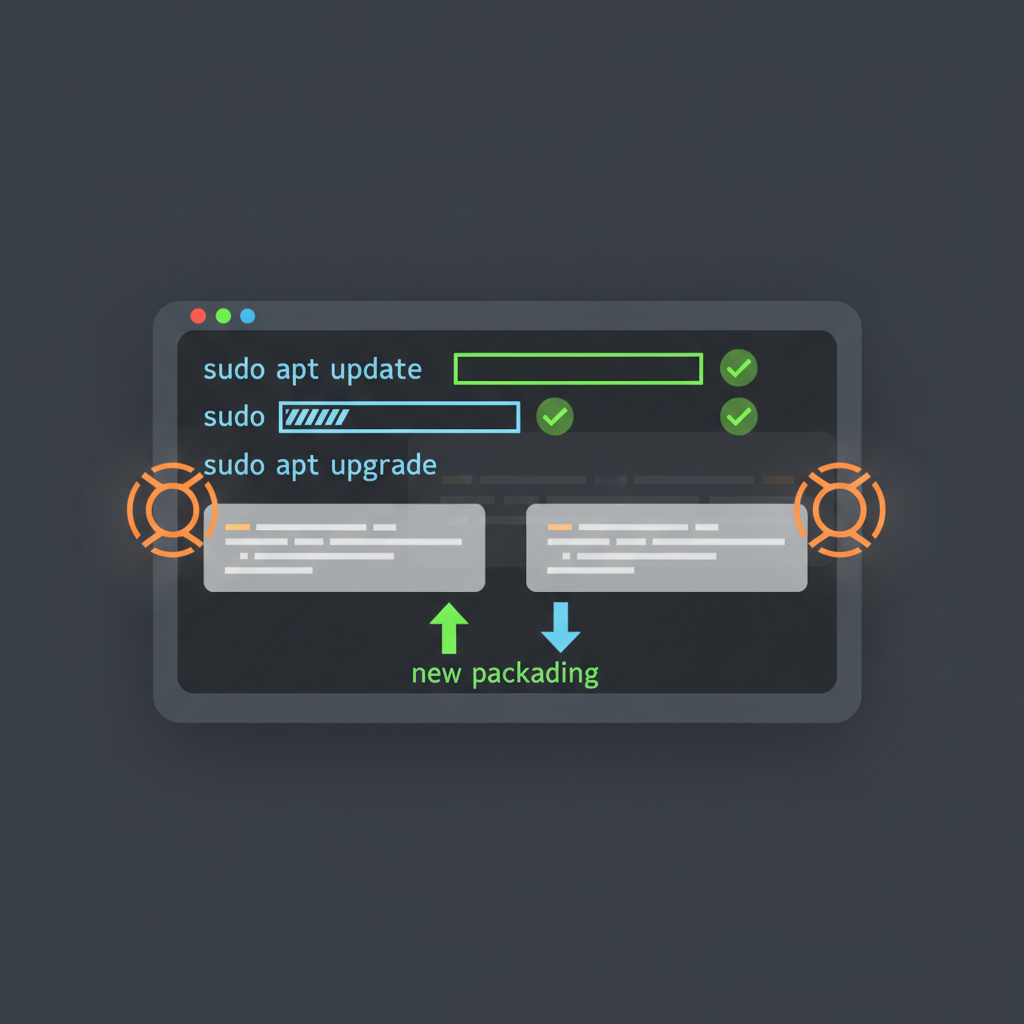

If you’ve ever stared at your terminal wondering why you need to run two separate commands just to update your Ubuntu or Debian system, you’re not alone. I spent my first week as a junior sysadmin blindly copy-pasting sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade without actually understanding what each command did.

Then one day, a package update broke a critical service during production hours. That was the moment I learned these aren’t just two steps in a ritual—they’re fundamentally different operations that every Linux admin needs to understand.

Here’s what you actually need to know about apt update vs apt upgrade, why running them in the right order matters, and how to avoid the mistakes I made early in my career.

What Does Apt Update Actually Do?

The apt update command doesn’t install or upgrade anything. Instead, it refreshes your system’s package index—think of it as updating your system’s catalog of available software.

When you run sudo apt update, your system contacts all the repositories listed in /etc/apt/sources.list and downloads the latest package information. It’s checking: What’s the newest version of each package? What new packages are available? What dependencies have changed?

This is purely informational. No packages get installed, no services get restarted, nothing on your system changes. You’re just bringing your system’s knowledge up to date.

apt update at the start of every troubleshooting session, even if I’m not planning to install anything. It ensures I’m working with current package information if I need to check versions or dependencies.What the Output Tells You

When you run apt update, you’ll see lines like this:

Hit:1 http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu jammy InRelease Get:2 http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu jammy-updates InRelease [119 kB] Get:3 http://security.ubuntu.com/ubuntu jammy-security InRelease [110 kB]

Each “Hit” means your cached package list is still current. Each “Get” means apt is downloading updated package information. If you see errors here, it usually means a repository is unreachable or your sources.list has issues.

What Does Apt Upgrade Actually Do?

Now apt upgrade is where things actually happen. This command takes the package information from your last apt update and uses it to upgrade installed packages to their newest available versions.

Running sudo apt upgrade will:

- Download new package versions that have updates available

- Install those updated packages

- Replace older versions with newer ones

- Keep your existing packages intact (it won’t remove anything)

The key behavior of apt upgrade is that it’s conservative. If upgrading a package would require removing another package or installing a new dependency, apt upgrade will skip that upgrade entirely. It plays it safe.

When Apt Upgrade Holds Packages Back

Sometimes you’ll see messages like “The following packages have been kept back.” This happens when a package update requires changes that apt upgrade won’t make on its own—usually installing new dependencies or removing conflicting packages.

I see this most often with kernel updates and major library upgrades. It’s not a failure; it’s apt being cautious.

Why You Need to Run Them Together (and in Order)

Here’s where new admins get tripped up. Running apt upgrade without running apt update first means you’re upgrading based on outdated package information.

Your system might have package indexes from three weeks ago. When you run apt upgrade with stale data, you’ll install “new” versions that are actually already outdated. You’re not getting the latest security patches or bug fixes—you’re installing whatever your system thought was current weeks ago.

This is exactly how I missed a critical SSH security update on a production server once. I’d been running apt upgrade regularly but hadn’t updated the package list in over a month. The security patch was available, but my system didn’t know it existed.

According to recent statistics, Ubuntu powers nearly 34% of Linux installations, and Debian-based systems combined represent nearly half of all Linux distributions. That means understanding apt isn’t niche knowledge—it’s fundamental for almost half the Linux ecosystem.

apt update && apt upgrade regularly is one of the simplest ways to close security gaps.The Command You Should Actually Use

Most admins chain these commands together:

sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade

The && operator means “run the second command only if the first succeeds.” This is the pattern I use daily. It ensures your package index is current before attempting any upgrades.

For a completely hands-off approach, you can use the -y flag to automatically answer “yes” to prompts:

sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade -y

I use this in automation scripts, but be careful with it on production systems. You want to review what’s being upgraded, especially for kernel updates or major version changes.

When to Use Apt Full-Upgrade Instead

There’s a third option: apt full-upgrade (or the older apt-get dist-upgrade). This is more aggressive than apt upgrade.

The full-upgrade command will:

- Install new packages if needed to satisfy dependencies

- Remove packages if they conflict with upgrades

- Handle those “kept back” packages that

apt upgradeskips

I use full-upgrade when I’m doing major system updates or when I see packages held back that I know need updating. But I always review what it plans to remove first. Blindly running full-upgrade can remove packages you actually need.

Common Mistakes (That I’ve Made)

Let me save you from some painful learning experiences.

Running Upgrades During Peak Hours

I learned this one the hard way. Package upgrades can restart services automatically. That web server update? It might restart Apache or Nginx. That database library update? Could trigger a brief connection interruption.

Schedule your apt upgrade runs during maintenance windows, not at 2 PM on a Tuesday when your app is getting hammered with traffic.

Ignoring Held Packages Indefinitely

When apt upgrade tells you packages are being “kept back,” don’t just ignore it forever. Those are often security updates or important bug fixes. Check what’s being held and why:

apt list --upgradable

Then decide whether to run apt full-upgrade or upgrade specific packages individually.

Not Cleaning Up Afterward

Over time, apt accumulates downloaded package files and old dependencies. After running upgrades, clean house:

sudo apt autoremove sudo apt clean

The autoremove command removes packages that were installed as dependencies but are no longer needed. The clean command clears out downloaded package files from /var/cache/apt/archives/.

I’ve seen systems with 10+ GB of cached packages that were never cleaned up. On disk-constrained servers, that matters.

Apt vs Apt-Get: Does It Matter?

You’ll see both apt and apt-get in tutorials. Here’s the real difference: apt is the newer, more user-friendly command designed for interactive use. It has progress bars, colored output, and combines the most commonly used features of apt-get and apt-cache.

For daily use on the command line, use apt. For scripts and automation where you need stable, predictable output, use apt-get. The core functionality is the same.

I switched to apt for all my interactive work years ago and haven’t looked back. The progress bars alone make it worth it when you’re upgrading hundreds of packages.

Automating Updates Safely

On servers, you probably want some level of automated updates. Ubuntu offers the unattended-upgrades package that can automatically install security updates.

Install it with:

sudo apt install unattended-upgrades sudo dpkg-reconfigure -plow unattended-upgrades

This sets up automatic security updates but leaves feature updates for manual installation. It’s a reasonable middle ground between security and stability.

I configure this on every server I manage, then still run manual updates weekly to catch non-security packages. Having worked through security incidents caused by unpatched systems, I’m militant about keeping things updated.

What About Desktop Systems?

On desktop Ubuntu, the Software Updater GUI basically runs apt update and apt upgrade for you with a nice interface. But I still drop into the terminal for updates because:

- It’s faster

- I can see exactly what’s being updated

- I can chain cleanup commands immediately

- I’m a terminal guy—it’s just muscle memory at this point

Troubleshooting Common Apt Problems

Sometimes apt update fails. Here are the issues I see most often:

Repository Signature Errors

If you see “The following signatures couldn’t be verified,” it means apt can’t validate the repository’s GPG key. This happens when you add third-party repositories without importing their keys properly.

Find the key for your repository and import it, or remove the problematic repository from your sources list.

Failed to Fetch Errors

Network issues, dead repositories, or outdated Ubuntu releases cause these. Check your network connection first, then verify the repositories in /etc/apt/sources.list are still active.

If you’re running an old Ubuntu version that’s reached end-of-life, you’ll need to switch to the old-releases repository or upgrade to a supported version.

Lock File Issues

The dreaded “Unable to acquire the dpkg frontend lock” error happens when another process is using apt. Usually, it’s the automatic updater running in the background.

Check what’s running:

ps aux | grep -i apt

Wait for that process to finish, or if it’s genuinely stuck, carefully remove the lock file. But only after confirming nothing legitimate is using it.

Best Practices I Follow

After a decade of managing Linux systems, here’s my actual workflow:

On servers: I run apt update && apt upgrade weekly during scheduled maintenance. Security updates get applied immediately via unattended-upgrades. Before major application deployments, I check service status and hold any packages that might cause conflicts.

On development machines: I update packages whenever I start a session where I’m installing new tools. I’m less concerned about update timing since I’m not serving production traffic.

Before any system changes: I run apt update first, even if I’m not upgrading anything. Current package data prevents weird dependency issues when installing new software.

I also maintain a simple monitoring script that checks for available updates and alerts me if security patches have been available for more than 24 hours. You can build something similar with a simple script that parses apt list --upgradable output.

The Official Documentation

While I’ve shared what works from practical experience, the official Ubuntu package management documentation is worth bookmarking. It’s comprehensive and stays current with each Ubuntu release.

For command reference and advanced usage, the apt command cheat sheet at nixCraft has saved me countless times when I need to remember a specific flag or option.

Final Thoughts

Understanding apt update vs apt upgrade isn’t just about knowing two commands. It’s about understanding that your Linux system needs both fresh information and fresh software to stay secure and functional.

Run apt update to refresh your package catalog. Run apt upgrade to install updates based on that fresh data. Do both regularly, in that order, and you’ll avoid most of the package management headaches that trip up new Linux users.

The time you invest in understanding these fundamentals pays off every single day you work with Debian-based systems. It’s the difference between blindly running commands and actually knowing what your system is doing.

And trust me—when you’re troubleshooting a production issue at 3 AM, that knowledge matters more than you’d think.